The following article is adapted from the ESV Archaeology Study Bible—a new study tool that roots biblical text in its cultural and historical context.

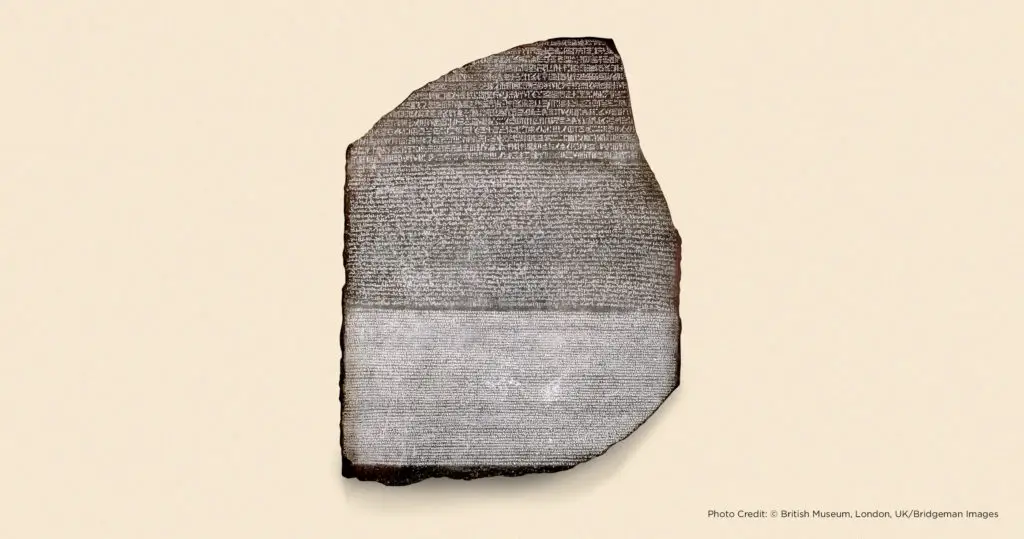

1. Rosetta Stone

In 1798, Napoleon invaded Egypt. He brought with him a scientific team of scholars and draftsmen to survey the monuments of the land. The most important find of the expedition was the Rosetta Stone. It proved to be valuable as the key to deciphering ancient Egyptian hieroglyphics.

The stone dated to the period of Ptolemy V (204–180 BC) and was inscribed in three scripts: demotic, Greek, and hieroglyphic. The Greek, well known to scholars at the time, proved to be a translation of the ancient Egyptian language on the stone. Translation of hieroglyphics marked the beginning of the study of ancient Egyptian texts and grammar and provided the basis for modern Egyptology studies.

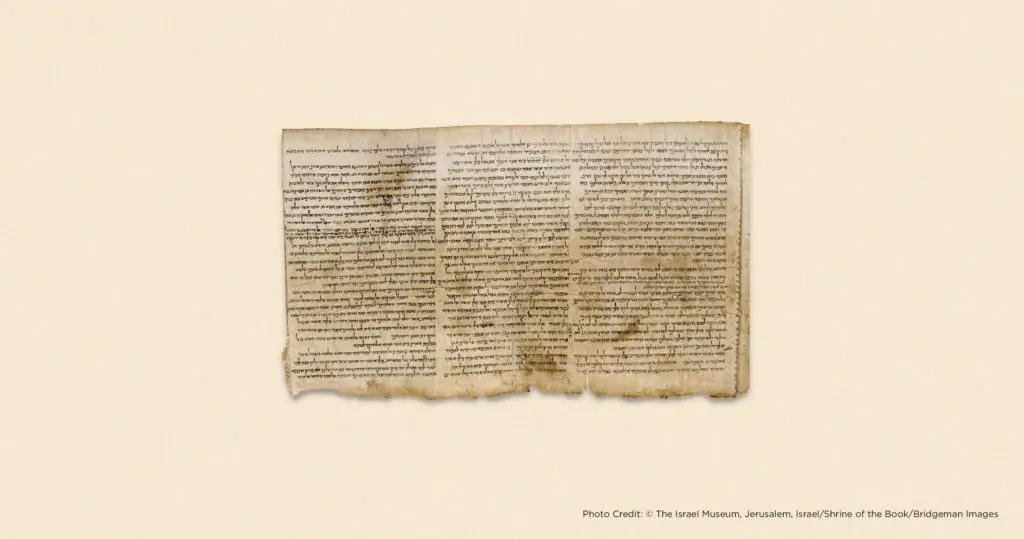

2. Dead Sea Scrolls

In 1947, shepherds stumbled upon a cave in a rugged, arid area on the western side of the Dead Sea. What they discovered was soon proclaimed the greatest archaeological find of the twentieth century. Over the next few years, other, similar remote caves in the area were found. What did these caves contain? Over 800 fragmentary documents, mainly consisting of Hebrew writings on leather (with a few on parchment), including fragments of 190 biblical scrolls. Most of these are small, containing no more than one-tenth of a book; however, a complete Isaiah scroll has been found. Almost every OT book is present, and there are also other writings valued by the community that dwelt in those caves. It appears the earliest scrolls date to the mid-third century BC, and most to the first or second centuries BC.

Perhaps the greatest contribution of this find is to our understanding of the transmission of the biblical text. It is encouraging to note that the differences are minimal between the OT texts of the Dead Sea Scrolls and various editions of the Hebrew texts produced a thousand years later and used today, involving the smallest textual details. The meaning of the text itself is not affected by these differences.

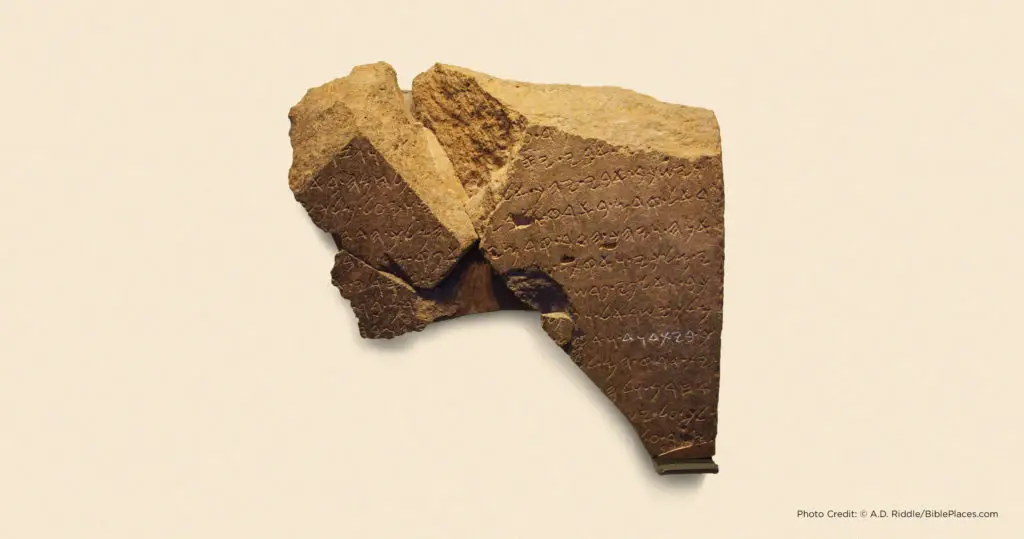

3. Tel Dan Inscription

In 1993, excavators at Tel Da uncovered an inscription with the word BYTDWD on it. They convincingly argued that the word means “house of David” and dates to the ninth century BC. The inscription had been sealed by a later Assyrian destruction layer firmly dated to 733/722 BC. An ash layer is an archaeologist’s dream. Anything sealed beneath it must be dated earlier, because there is no possibility of intrusion by later artifacts. Pottery directly beneath the destruction level dates to the ninth and eighth centuries BC, and from this period the so-called House of David inscription must have come.

Although some scholars have attempted to explain away the inscription by asserting BYTDWD is either a place-name or a designation for a temple of a deity, it probably refers to the house of lineage of David, the second king of the united monarchy and arguably the most significant ruler in the history of Israel. Additional evidence is the likely appearance of the term BYTDWD on the Mesha Stela/Moabite Stone, also dating to the ninth century BC.

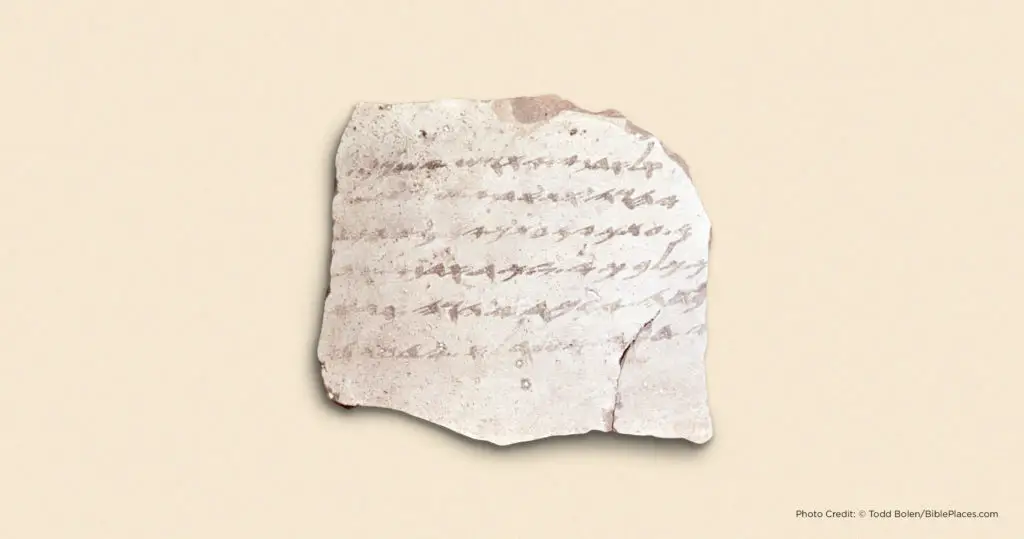

4. Ketef Hinnom Scrolls

In 1979, Israeli archaeologist Gabriel Barkay was excavating a burial cave at Ketef Hinnom, just southwest of Jerusalem. The tomb was a typical Late Iron Age (c. late 7th century BC) burial structure. The typical Judean burial at this time took place in a rock-cut cave. When a person died, he was placed on a burial bench in the tomb along with personal items such as vases, jewelry, or trinkets. Once the body decayed, the bones of the person were placed in a box beneath the burial bench. When the team began to excavate the box, they came upon two small silver scrolls. Since the scrolls were metal, the archaeologists had a difficult time unrolling and deciphering their text. They began with the larger of the two scrolls, which took three years to unroll. When unrolled, it measured only three inches (7.6 centimeters) long. When they finished, they noticed the scroll was covered with very delicately etched characters. The first word they were able to decipher was the name “Yahweh.” After much work, they were able to read the entire scroll. It contained the priestly benediction from Numbers 6. The smaller scroll also contained the benediction from Numbers 6. It took so long to unroll and decipher the scrolls that the material was not published until 1989.

These two scrolls are relatively unknown, but they can be seen today in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem. They are the earliest known citations of biblical texts in Hebrew. They predate the earliest Dead Sea Scrolls by more than four hundred years and are thus helpful in matters of textual criticism. Many authors have argued that the priestly benediction was written after the exile, with its earliest date from the fourth century BC. Now we have physical examples of the benediction from the late seventh century BC. In addition, the discovery of two plaques with the same benediction in a buried site underscores the centrality of the priestly benediction to the religion of the Israelites.

5. Moabite Stone

In 1868, a missionary in Jerusalem found a stone tablet for sale that appeared to be from ancient times. The sellers broke the tablet into a number of pieces to sell them one at a time to make more money. Fortunately, a copy of the tablet was made prior to the break (this copy is in the Louvre today). On the tablet is a text written in Moabite dating to the ninth century BC. It was perhaps a victory stone erected by King Mesha to commemorate his military achievements. The text begins, “I am Mesha son of Chemosh, king of Moab.”

Prominent in the text is the king’s version of a war fought with Israel in 850 BC, in which Moab revolted against King Jehoram of the northern kingdom of Israel soon after the death of Ahab. Of particular interest is that the Bible records the same incident in 2 Kings 3. The two accounts differ in perspective. Mesha emphasizes his victories over Israel in capturing cities under Israelite control. The biblical writer, to the contrary, highlights Israel’s successful counter attacks against the Moabites.

6. Lachish Letters

In the 1930s, J. L. Starkey excavated the site of Lachish. He discovered a layer of debris heavily destroyed and burned with fire at the hands of the Babylonians under Nebuchadnezzar in 589/588 BC. Starkey unearthed eighteen ostraca in the burnt debris of a guardroom between the inner and outer gates of the city. An ostracon is an inscription written in ink on pottery sherds. Most of the ostraca were correspondence, although a few were lists of names. The contents of the ostraca were fragmentary, and only a third of them are sufficiently preserved to be intelligible. The date of the ostraca is generally immediately prior to the destruction of Lachish by the Babylonians.

A number of the letters are written by a man named Hoshaiah to a military commander named Yaosh. The common interpretation is that Hoshaiah was the commander of a fortress outside Lachish writing to Yaosh, the commander of Lachish. Other commentators believe Hoshaiah was the military chief of Lachish and Yaosh a high official in Jerusalem. One of the letters closes with the statement, “Let [my lord] know that we are watching for the signals of Lachish, according to all the indications which my lord hath given, for we cannot see Azekah.” Hoshaiah was referring to signal fires from one Judean city to another, and the context appears to be the Babylonian assault soon to come.

7. Epic of Gilgamesh

In 1872, George Smith announced he had discovered an Assyrian account of a flood among tablets stored in the British Museum from excavations of mid-seventh-century-BC Nineveh. Called the Epic of Gilgamesh, the story comprises twelve tablets, with one tablet containing a tale of a great deluge. The hero of the flood, a man named Utnapishtim, relates an episode to Gilgamesh. He explains how the god Ea warned him about an approaching judgment and told him to build a boat to save his life from the watery onslaught. As the tale unfolds, the epic in some respects is nearly identical to the biblical narrative of Noah in Genesis 6–9. This discovery created quite a stir among biblical scholars of the nineteenth century, and even today scholars continue to puzzle over and debate the obvious parallels between the two.

8. Hezekiah’s Tunnel

The most dependable water source for the city of Jerusalem during the Israelite settlement was the Gihon Spring. However, its location outside the city walls was problematic. During an attack or siege, the inhabitants were cut off from their vital water source. In 1867, explorer Charles Warren discovered a vertical shaft cut through bedrock allowing the people of Jerusalem to reach the waters of the Gihon Spring from behind the city walls. This shaft was probably built originally by the Jebusites and may be how David’s soldiers captured the city from them (2 Sam. 5:6–8). A new water system employing part of the earlier one was built by Hezekiah near the end of the eighth century BC due to an Assyrian military threat. Hezekiah’s tunnel sloped gently away from the Gihon Spring to allow water to flow from it to the Pool of Siloam inside the city walls.

Hezekiah’s tunnel was cut by two teams digging toward each other from opposite ends. It was not chiseled in a straight line but was serpentine due to frequent shifts in terrain. The two teams made adjustments as they drew near each other and heard the picks of the other team. An inscription twenty feet (six meters) from the Siloam Pool has been discovered that describes the meeting of the two cutting teams.

9. Crucified Man at Givat Hamivtar

We are well aware of Roman methods of crucifixion of the first century AD—not only from written records, but also from the remains of a crucified man discovered at Givat Hamivtar, a site just outside Jerusalem. The cross consisted of two parts: the upright bar, called the stipes crucis, and the horizontal bar, called the patibulum. The crucified man was placed with his back over the stipes crucis, and his hands were nailed to the patibulum. According to archaeologists, the nails must have been driven through the wrist because the palms could not have supported the man’s weight.

He was affixed to the cross also by his feet, in a way different from what is commonly thought. The Roman executioner made a crude, rectangular frame of wood in which the heels of the victim were pressed. Then an iron nail was driven through the right part of the frame, through the man’s calcanei—the largest tarsal bones in the foot—and then through the left part of the frame. The free end of the nail was then bent by hammer blows. This find gives archaeologists further insight into Roman crucifixions.

10. Ugaritic Texts

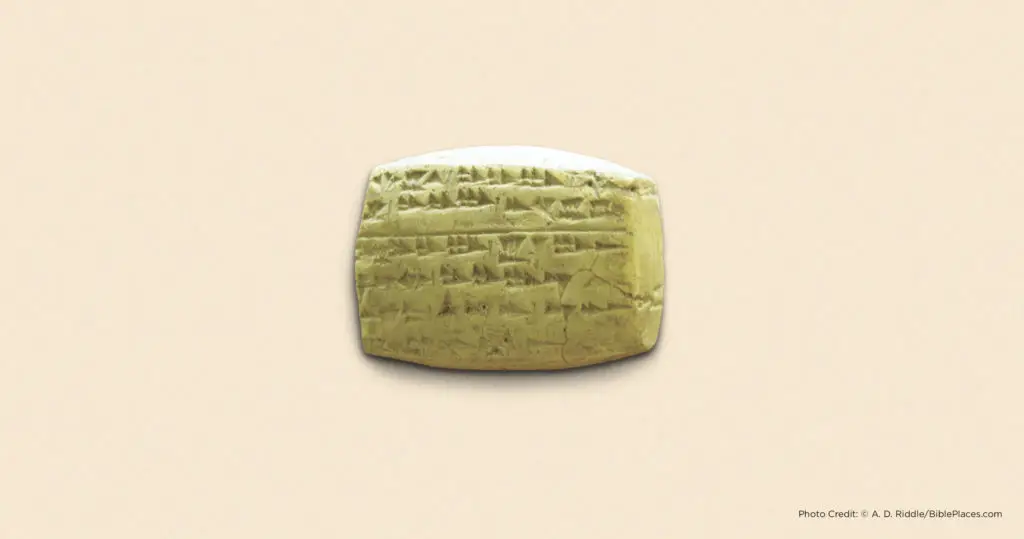

A great majority of Canaanite texts come from the site of Ugarit (modern-day Ras Shamra), on

the northern coast of Syria along the Mediterranean Sea. Ugarit was a prominent Canaanite city-state of the second millennium BC. Major excavations have taken place at the site since 1929. A most important find at Ugarit are hundreds of texts discovered in the palace and temple areas. More than 1,500 of those tablets have been published. Ugarit reached its height in the fifteenth to thirteenth centuries BC, the period in which written literature at the site flourished.

The city met its final fate at the hands of Mediterranean enemies, who destroyed the site around 1200 BC. The importance of the Ugaritic texts is the material they provide concerning Canaanite religion. Their mythic texts help us understand the religious context of the OT, including many parallels between Canaanite and Israelite religious practices. In addition, the languages of Ugaritic and Hebrew are quite similar, and thus Ugaritic provides insight into the development and grammar of Hebrew.

Written By: John D. Currid.

This article was originally published on Crossway.